Making Noise About Silent Film Series Lecture #4

From the Nickelodeon to the Movie Palace

The Phenomenon of Early Movie Exhibition

by Ken Fox

Delivered Saturday, May 21, 2022, at the Dryden Theater, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY

This final presentation in the Making Noise About Silent Film: Conversations about Cinema, Culture & Social Change Lecture Series looks at the evolution of cinema from the earliest still image projections to the movie “palaces” and the ways that this evolution reflected the stratification of American society. As the technology developed to transform movies into the first mass market entertainment for Americans, promoters targeted lower-class and immigrant audiences but also courted women viewers, a development that would help to change perceptions of women and reshape their participation in family, business, and political life. It was co-sponsored by the George Eastman Museum.

The Emergence of Cinema

I would like to begin with a few words about the research that I did for this presentation. Research has a way of taking on a life of its own, and I think that is how it should be. Months ago, I wrote the description of what I originally wanted this talk to be—“From the Peep Show to the Picture Palace,” how we got from one to the other during the early decades of cinema. But as I got to work, I found it difficult to leave the 19th century. Thinking about the primordial stew from which cinema as a practice grew doesn’t really lend itself to linear pathways. There are so many scenic detours and alternate routes, some of which I plan to share with you in this presentation.

Recommended reading: Charles Musser, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907 (University of California Press, 1994).I can think of no better way to start any discussion of early cinema in the United States than by recommending Charles Musser’s essential book, The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907. It was written at a time when there was still so much we didn’t know about cinema’s earliest years, a time which until only recently wasn’t given the kind of academic attention it was due. So this book came as a real eye opener. It runs a little over 600 pages, but it’s immensely readable and full of illustrations. But the biggest take-away for me, the point which has really stuck with me ever since I first read it, is right there in the title: “The Emergence of Cinema.” Musser quite deliberately avoids using works like “birth” or “invention” or “the starting point of cinema.” The very first point he’s keen to make is that there was no “original moment” for what we call cinema.

And here I should really hit pause for a moment and offer a definition of what I mean when I use the term “cinema,” as opposed to the less pretentious sounding “motion pictures” or “moving images.” “Motion Pictures” are certainly an important part of cinema, but it’s more than that. To me, cinema is a complex experience. So, my definition of cinema is the projection of moving images onto a screen, before an audience of more than one. It’s essentially a screen practice that requires projection, and, crucially, a group of spectators, even if it’s only two. I sometimes like to add “paying” audience members as a reminder that commerce has, from the outset, driven and determined cinema—the forms it would eventually take, the spaces in which it occurred, and the social groupings it helped form and inform.

Cinema’s Origin Myth

The Arrival of the Train at the Ciotat Station (1895, dir. Auguste & Louis Lumière).So briefly back to this notion of “the birth of cinema.” If this screen practice has an origin myth, it’s probably the one involving the first public screening of Auguste and Louis Lumière’s fifty-second-long black-and-white film The Arrival of the Train at La Ciotat Station. We’re all probably familiar with the story of the poor, naive Parisian audience of 1895—the year we often use to celebrate cinema’s anniversary—who mistook the film’s oncoming locomotive for an actual train. Terrified, they bolted for the exits.

It’s a good story, and like all good stories, it can’t possibly be true. There’s no contemporary account of it happening. The Arrival of the Train at La Ciotat Station wasn’t even on the bill that evening in December, 1895. (In fact, the Lumières’ first version of the film wasn’t shot until weeks later in January, 1896.) And more to the point, it’s very hard to believe that an audience of sophisticated Parisians could have mistaken a grainy, dimly-lit, three-foot high, black-and-white silent image of a train for the real thing. By the 1890s, Parisian audiences would have been quite familiar with all manner of visual novelties, including projected photographs and moving pictures, which they would have viewed via a peep-show mechanism. They may have been amazed by the projection, thrilled by the sensational composition of the shot, but they would hardly have been fooled.

“Projecting moving images for an audience was really just the latest development in a series of ‘screen practices’ that had been entertaining and educating audiences for centuries—at least as far back as the 17th century.”

— Ken Fox

Early Screen Projection Practices

This familiarity with other contemporary screen practices speaks to Musser’s idea of cinema’s “emergence.” We can still consider “starting points,” but it’s really much more productive to think about cinema in terms of its continuity with the past rather than its differences. From this perspective, projecting moving images for an audience was really just the latest development in a series of “screen practices” that had been entertaining and educating audiences for centuries—at least as far back as the 17th century, when the magic lantern (or laterna magica) was first developed.

The Magic Lantern

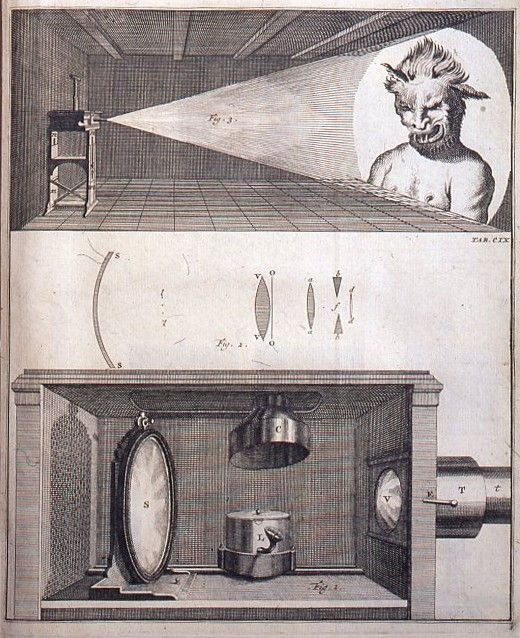

Here we see one of the earliest depictions of an image projected by the magic lantern, from the 1617 edition of Kircher’s The Art of Light and Shadow, the second oldest book in the library of the George Eastman Museum. The first is Kircher’s 1646 edition of the same work.

Title page of Athanasius Kircher, Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (1671, Revised and Expanded Edition. (The Rare Books Collection, The Richard and Ronay Menschel Library/George Eastman Museum)Page from Athanasius Kircher, Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (1671, Revised and Expanded Edition. (The Rare Books Collection, The Richard and Ronay Menschel Library/George Eastman Museum)Early Magic Lantern Technology

The magic lantern was a device not unlike the slide projectors we once used for presentations before the advent of PowerPoint. Simply put, magic lanterns used a light source to project images painted or printed on a transparent plate, usually made of glass.

A page of Willem Gravesande’s 1720 book Physices Elementa Mathematica, showing Musschenbroek’s lantern.Jan van Musschenbroek’s magic lantern (ca. 1720), one of the oldest extant examples.Magic Lantern Technology Evolves

Triunal magic lantern projector, J. Ottway & Son, 1891, Francis Collection, Museums Victoria. (Courtesy Museums Victoria Collections, Photographer Jon Augier)Using magic lanterns with multiple lenses like the one seen here, lanternists could perform amazing transformations through dissolves. And with ingeniously designed slides made of multiple layers of glass that could shift and slide, some with cranks that could rotate superimposed projected images, the magic lantern could very convincingly simulate movement.

Magic Lantern Audiences

During the 17th and 18th centuries, magic lanterns were largely used for entertainment purposes, sometimes in private homes of the wealthy, other times in public spaces courtesy of travelling showmen, musicians, and storytellers.

Magazine illustration featuring Punch, projected by magic lantern in a domestic setting, ca. 1830. (Courtesy Martyn Jolly)Robertson’s Phantasmagoria

In the late 17th century, the physicist and stage musician Étienne-Gaspard Robert (who adopted the stage name “Robertson”) terrified audiences with his popular phantasmagoria, in which he used a complex arrangement of hidden magic lanterns to project ghostly images on moving screens and floating clouds of acqua fortis—nitric acid, actually—all set to the chilling accompaniment of a glass harmonica.

Étienne-Gaspard Robertson’s “Phantasmagoria at the Cours des Capucines in 1797.” (Engraving by Louis François-Lejeune, from Mémoires Récréatifs, Scientifiques et Anecdotiques, by Étienne-Gaspard Robertson (Paris: Chez l‘auteur et à la Librairie de Wurtz, 1831)Magic Lanterns as Edutainment

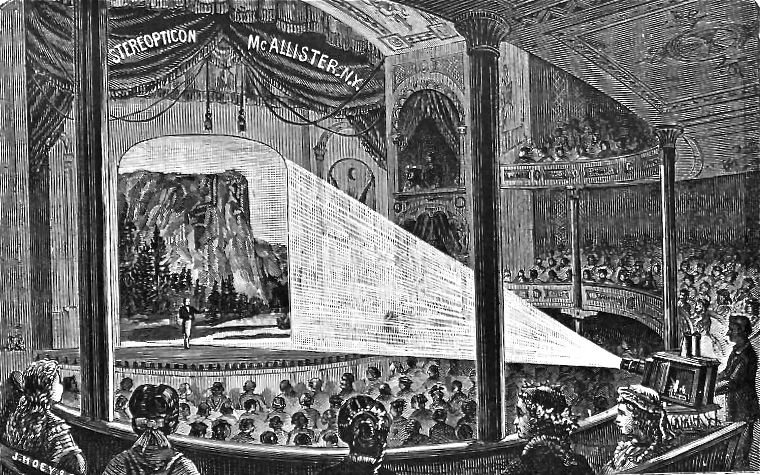

Frontispiece to T. H. McAllister’s Catalogue, published in New York in 1887. (Courtesy Victorianweb.org)But magic lantern shows weren’t always about entertainment, or if they were, they were often given the gloss of educational respectability. (This “obvious entertainment posing as education” would remain a constant well into the 20th century, especially when it came to cinema.)

Edifying lectures illustrated with magic lantern projections became particularly popular with 19th-century audiences, especially after 1849, when the Langenheim Brothers of Philadelphia used Niepce de Saint-Victor’s method of printing photographs onto glass to mass produce photographic lantern slides.

Catalogue of Langenheim’s Magic Lantern Slides, ca. 1890. (George Eastman Museum, Photo Collection)Photographically illustrated public lectures on scientific and historical subjects soon became staples of theaters, lecture halls, Chautauqua tents, churches, and fraternal societies. Travelogues were particularly popular, as were photographs of famous persons, historical sites, and newsworthy events—educational without question, but entertaining as well. These illustrated lectures would only become even more popular once the projected images began to move.

Moving Images

So when exactly did images begin to move? Considering what we know about the capabilities of the magic lantern, images had been moving since at least as early as the 18th century. The 19th century saw drawn or painted images animated by devices like the zoetrope, the praxinoscope, the phenakistascope, and the Théâtre Optique, which used sequential images mounted on a strip of film painted on squares of clear gelatin and connected by a strip of cloth.

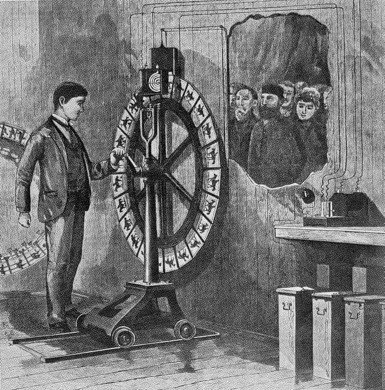

But if we’re talking about sequential photographs, exhibited in such a manner that the eye was tricked into interpreting what it was seeing as motion, then we are talking about first the electrotachyscope, which mounted chronophotographs of the kind taken by Eadweard Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Marey on a turning wheel, and Thomas Edison’s kinetoscope.

Electrotachyscope, 1886-1894. (Courtesy American Scientific)Kinetoscope, 1891-1893. (Courtesy American Scientific)The Invention of the Kinetoscope

Kinetoscope, Edison Manufacturing Company, 1894. (George Eastman Museum, Technology Collection)First demonstrated in 1891 for a contingent of society ladies, patented in 1893, and first commercially exhibited in 1894, the kinetoscope was invented by . . . it’s a little complicated.

Whether credit goes to William Kennedy Laurie Dickson or his employer, Thomas Edison, the fact remains that Edison’s already very famous name went on the thing, and it was hailed as the latest miracle from the Wizard of Menlo Park, though technically the Edison Studios were located in West Orange, New Jersey.

The American Society of Cinematographers describes the kinetoscope as “an early motion picture exhibition device, and the first to utilize sequential images printed on a strip of perforated, flexible, photographic film driven by sprockets and an intermittent movement.”

That flexible, photographic film was, of course, developed and manufactured by George Eastman, and the perforated strip of plastic that ran through the machine would remain largely unchanged for the next 100 years.

The Coin-Operated Phonograph

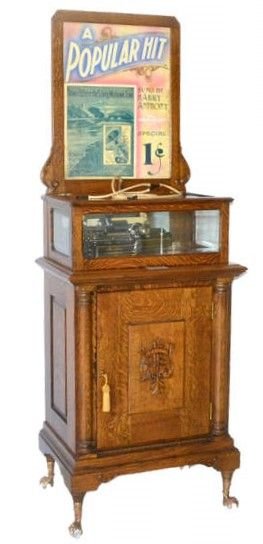

Coin-operated phonograph, Edison Eclipse, Edison Manufacturing Company, ca. 1903. (Courtesy Musical Treasures of Miami)Later, when he spoke about having invented the kinetoscope, Edison famously said that he wanted to do for the eye what the phonograph did for the ear. He could just as easily have been talking about his business model, though that was one thing he definitely did not invent himself.

Edison had originally intended for the phonograph to be used as a business machine, a dictation device, but it was far too complicated for office workers to use without extensive training, and it actually did a terrible job reproducing speech clearly and without distortion.

Edison lost interest, that is, until one enterprising investor named Louis Glass of San Francisco realized that the phonograph did a far better job as a “singing machine.” Glass soon began manufacturing and very successfully marketing these failed business machines as entertainment devices. Suddenly, Edison was interested again.

Glass outfitted the phonographs with nickel slots and listening tubes that transmitted the songs and speeches recorded on the cylinders to the listeners’ ears, and the coin-operated phonograph became the first automatic amusement machine.

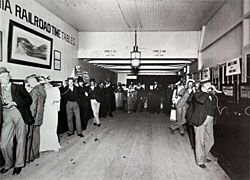

The Public Phonograph

Railroad station phonograph arcade. Unidentified photographer, undated. (Courtesy Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences)Louis Glass first placed these coin-operated phonographs in saloons and in the waiting rooms of ferry terminals. As the photograph shows, listeners at a train station would while away the minutes listening to phonographs as they waited for their trains to arrive. Other entrepreneurs, many of them traveling exhibitors, leased space in hotel lobbies, on fair midways, and at summer resorts.

The Public Phonograph Parlor

Recommended reading: David Nasaw, Going Out: The Rise and Fall of Public Amusements (Harvard University Press, 1999).As David Nasaw writes in his informative and hugely entertaining book Going Out: The Rise and Fall of Public Amusements:

“While the traveling exhibitors were exhibiting phonographs during the warm weather . . . parent companies had stumbled upon what appeared to be an ideal—and permanent—exhibition site in the central business districts. They had found that by grouping several machines together in a downtown ‘parlor,’ with full-time attendants to service the machines and make change, they could attract large numbers of customers from the streams of pedestrians who passed by day and night.”

White-Collar Workers Enjoy the Public Phonograph

Phonograph Arcade. Unidentified Photographer, undated. (Courtesy US Department of the Interior/National Park Service/Edison National Historic Site)And who were these pedestrians? In the business districts where the phonograph arcades were established, many were members of a new kind of working class: the white-collar worker.

Not quite manual laborers, yet certainly not “bourgeois,” the members of this modern, industrialized workforce were the clerical, low-wage workforce that kept the modern business office humming.

They sometimes had a few coins to spare, and, thanks to the standardization of pretty much everything about their day, from their work schedule to the commuter timetable that got them to work in the morning and back again at night, they had downtime to kill. They were often hurrying up only to wait, waiting and growing bored, grateful for some amusing distraction before the next train or trolley home.

Women and the Public Phonograph

Recommended reading: Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Temple University Press, 1986).And many of these pedestrians were women, still-single daughters of immigrant families who, particularly after the economic crisis of 1893, had no choice but to loosen their more conservative ideas about what constituted proper women’s work. No longer limited to domestic work within and outside their own homes, this new workforce made up a significant portion of that pedestrian traffic Nasaw cites as the purveyors of the phonograph, and later the kinetoscope parlors.

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT DIVERSE AUDIENCES

>>Film historians have noted that part of the growth of the nickelodeon can be attributed to attendance by children and women (and sometimes women with their babies and children). Why do you think that women were attracted to this new entertainment?<<

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT DIVERSE AUDIENCES

>>How did nickelodeons and early films help to “Americanize” immigrants?<<

The First Kinetoscope Parlor

Kinetoscope Parlor. Unidentified photographer, ca. 1895. Gelatin silver print. (George Eastman Museum)On April 14, 1894, brothers Andrew and George Holland opened the first commercial kinetoscope parlor in a storefront located at 1155 Broadway, New York.

It closely replicated the exhibition model set by the phonograph arcade. Ten machines were set up in two rows, with patrons paying 25 cents to see a row of five machines.

On the bill: Edison films, including clips of the strong man Sandow, and two films featuring Ena Bertoldi (Beatrice Mary Claxton), the music-hall contortionist.

The entrepreneurial Holland Brothers had previously been involved in publishing, bookselling, typewriters, steamship lines, and, not coincidentally, Edison phonographs.

Segregated Amusements

The amusement park and railroad station at Coney Island, ca. 1880. (Courtesy Wikipedia)On the weekends, the same commuters we met earlier, passing to and fro from work to home and back again, could ride some trolleys to the end of the line and spend the day at an amusement park. It was no coincidence that the trolley company and the owners of the parks were sometimes one and the same. In fact, early amusement parks, which were originally little more than picnic grounds and recreation areas, were originally known as trolley parks.

Postcard view of the Oakwood Park picnic grounds, Kalamazoo, Michigan, ca. 1914. Private collection. (Courtesy Kalamazoo Public Library)Leaving the city for a pleasant afternoon by the cooler air of a lake shore or seaside was once a pastime meant only for the rich. But for the mostly white working classes—including this new class of white-collar clerk—who had some allotted leisure time and cheap transportation, a day of pleasure was just a trolley ride away.

Whether or not these parks permitted Blacks to mingle with whites was in theory a matter of the segregation laws of the region. But, unsurprisingly, more often than not, many parks found ways to segregate or exclude Blacks and Asians entirely.

As Nasaw remarks, few parks had written racial policies. They didn’t have to. According to the white supremacist cultural mores of the time, entertainment venues that featured dancing, dining, and swimming, not to mention rides that, by design, tossed bodies against one another, had to be segregated.

Kinetoscopes at Hotels

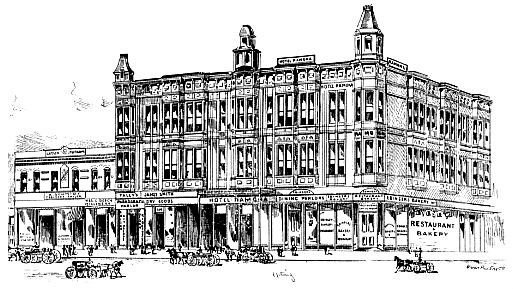

Hotel Ramona Lobby & the Environs. Unidentified photographer. (Courtesy Rutgers School of Arts and Sciences)Hotels also became a prime spot for kinetoscope machines. Hotels, which saw a boom in construction in the latter half of the 19th century, largely catered to guests in town on business or tourists taking in all the sights and amusements the city had to offer.

With time to kill before the 7:30 p.m. curtain lifted on a tony uptown theater, what better way for tourists to while away the minutes than in front of the kinetoscope, with each entertainment lasting no more than sixty seconds.

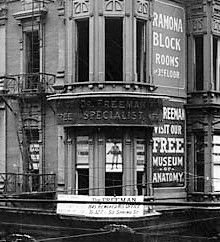

Pictured here is L.A.’s Hotel Ramona, on Spring Street. The building to the far left, which actually stood over the basement to the hotel, is Tally's Phonograph Parlor, owned and operated by the Texan huckster T. L. Tally.

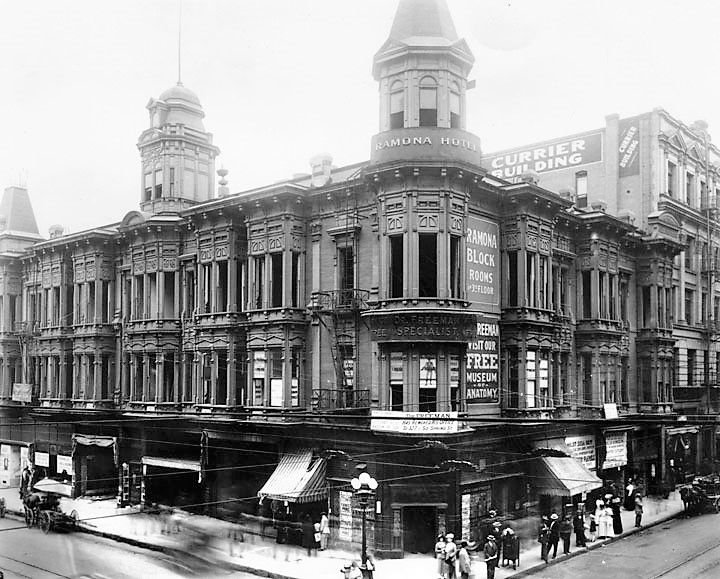

A relevant aside: here’s a photo of the Ramona taken from nearly the same position as the drawing. You can’t see Tally’s to the left, but if you look closely you can see something very interesting on the corner turret.

Exterior view of the Hotel Ramona, Los Angeles, ca. 1900. Unidentified photographer. (From the Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library)The Anatomical Museum

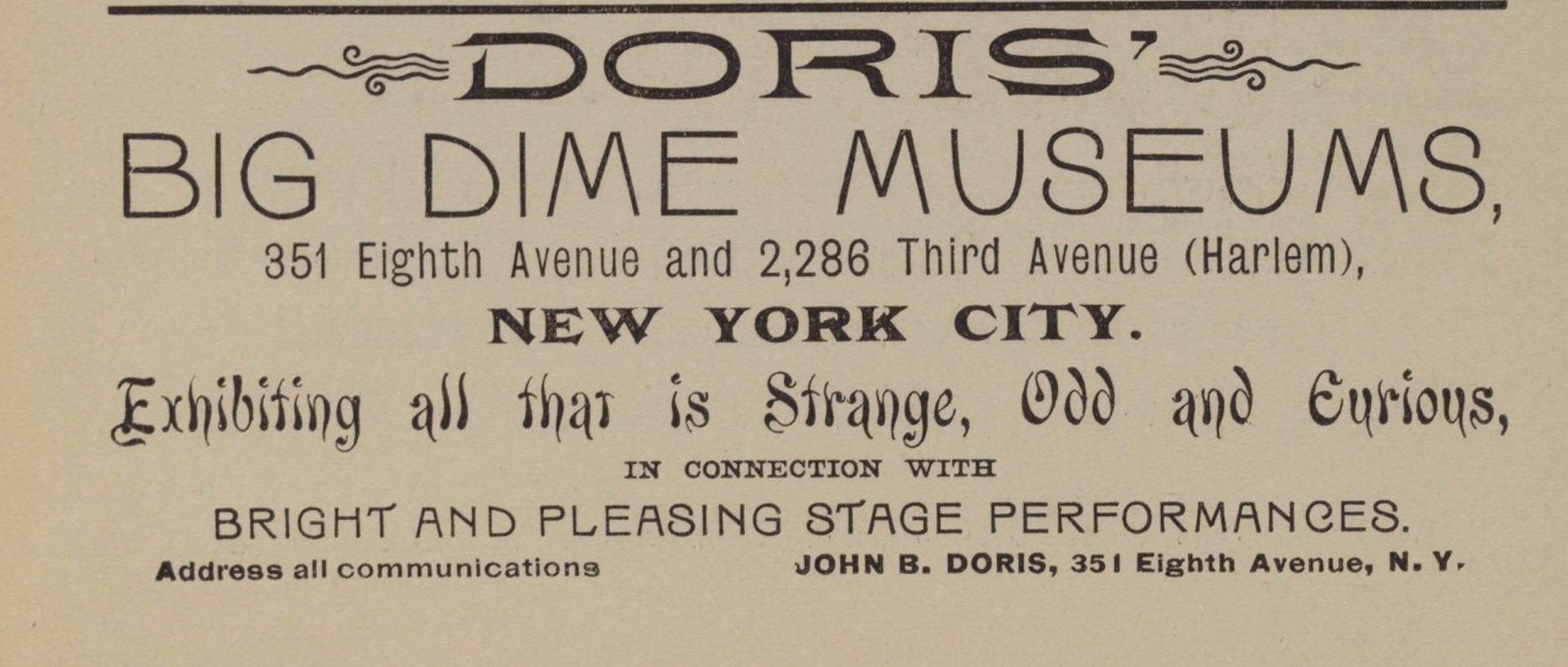

Dime Museum. Exterior view of the Hotel Ramona, Los Angeles. Unidentified Photographer, ca. 1900. (From the Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library)From the lettering on the cornice, it appears those corner windows belong to the offices of a “Dr. Freeman, Specialist.” Next to it, a sign: “Dr. Freeman: Visit Our Free Museum of Anatomy.” The “anatomical museum” was probably the most notorious type of the very popular “dime museum.” These weren’t museums in the sense that the George Eastman Museum or the Memorial Art Gallery are museums. They weren’t devoted to exhibiting art per se, unless one had a very, very broad definition of “art.” These were museums in the tradition of the Cabinet of Wonders, often as a jumble of attractions that were designed to thrill, amaze, and—in the case of the anatomical museum—horrify.

Advertisement in The New York Clipper Annual 1891. (New York: Frank Queen Publishing Company 1891)The most famous example of the dime museum was P. T. Barnum's American Museum in downtown Manhattan. Here one could see ancient relics, fake mermaids, human oddities like sword swallowers and people with disabilities exhibited as so-called “freaks,” magicians, and kinetoscopes. Many museums added a separate theater where specialty acts would perform—the dime museum was an important precursor to vaudeville—and eventually, films projected.

This lantern slide, probably projected between films in a nickelodeon, warns patrons against “museums” like Dr. Freeman’s. Lantern slide. United States Public Health Service, early 20th century. (Courtesy Common-place Journal/National Museum of Health and Medicine, Washington, D.C.)Dr. Freeman’s Museum was probably in a different league. While the anatomical museum had somewhat respectable roots in the Victorian interest in the body, by the time Dr. Freeman opened shop many of these attractions had become little more than a seedy excuse to gaze upon grotesque wax models of “where babies come from.” It did, however, maintain the veneer of educational value, not unlike the illustrated lectures before them and the exploitation films that would soon follow.

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT DIVERSE AUDIENCES

>>How did the dime museums, which were so popular in the late 19th century, help to give rise to moving pictures?<<

Tally’s Kinetoscope and Phonograph Parlor

Tally’s Kinetoscope Theater, ca. 1898. (From the Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library. Courtesy Los Angeles Public Library)I would just like to return for a moment to Tally’s, just next door to the Ramona Hotel, for an extraordinary interior shot. On the left, you can see six kinetoscopes in a row. And if you look very carefully, you can see a sign on the side of the machine closest to the camera advertising the fight film Corbett and Courtney Before the Kinetograph, a staged six-round match between professional boxers James J. Corbett and Peter Courtney that was shot at Thomas Edison’s Black Maria in West Orange, New Jersey, in 1894. It was exhibited as six reels, one reel per round, and spectators would move from one machine to the next, five cents per round, or thirty cents to watch all six.

To the right of the frame is the coin-operated, single-user phonographs, and in the back, according to the large sign above the curtain doorway, is what Tally called the “Mammoth Projecting Kinetoscope.” On the sign just inside the curtain, right behind the American flag, we can make out parts of the words “Edison,” “Reproduction,” and “Warships,” which tell us that the film being exhibited in the back is Edison’s short “New York Welcomes the Warships.”

Vaudeville and the Moving Image

The Empire Theater, Rochester, NY. Corner of East Main Street and Clinton Avenue, ca. 1903. (Courtesy of elmorovivo/cinematictreasures.org)As I mentioned, the dime museum’s theater, along with minstrel shows, concert saloons, and low-brow variety shows, were an important precursor to vaudeville. It is virtually impossible to overstate vaudeville’s importance, not just as a venue through which moving images passed but as a cultural force that shaped people’s desires and expectations.

From roughly 1880 until well into the 20th century, vaudeville remained the dominant form of entertainment in the United States. By 1880, when impresario Tony Proctor cleansed vaudeville of the bawdy, tawdry “male only” acts that were holdovers from saloon concerts, vaudeville had become a form of entertainment suitable to a so-called “double audience”—an audience comprised of both men and women. And, as we saw with the phonograph and kinetoscope parlors, from a profit-making standpoint, welcoming women was crucial.

One successful vaudeville theater was the Empire Theater, originally known as the Wonderland, located at the northeast corner of East Main Street and North Clinton Avenue in Rochester, New York, which was in operation from 1891 to 1904.

Vaudeville Offerings

May Bragdon Diary, December 27, 1897. Courtesy Rare Books and Special Collections and Preservation, Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester)Vaudeville’s success was largely due to several innovations of its own invention. Perhaps most important is that the vaudeville program was modular, made up of series of unrelated acts, each running about ten to fifteen minutes long. Since there was nothing really linking them together, they could be shuffled and rearranged, with the headliner usually appearing in the second-to-last slot.

This insert attached to a page from the diaries of Rochesterian May Bragdon (which have been digitized and are available online as part of an extraordinarily rich digital project on the University of Rochester’s library website) provides an idea of what was on offer at an upscale vaudeville house. There’s Mudge & Morton, “High-class musical entertainers”; Loney Haskell, a mimic; Abbaco, “The Original Acrobatic Tramp”; and so on.

But vaudeville also included a number of purely visual novelties, perfect for opening acts when audiences were still noisily entering the theater. Among them: the pantomime-spectacle; “dumb” playlets; shadowgraphy; lantern slide presentations; “living pictures”; “living photographs”; projected motion pictures (cinema).

We like to say that cinema was born in the United States on April 23, 1896, at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in New York City, a vaudeville house. But we also know that movies were projected—cinema took place—in Rochester, four months earlier at the Wonderland Theatre.

“It is virtually impossible to overstate vaudeville’s importance, not just as a venue through which moving images passed but as a cultural force that shaped people’s desires and expectations.”

— Ken Fox

Racial Segregation at the Movie Palace

“Mississippi at the State Fair.” John T. McCutcheon, Chicago Tribune, September 9, 1904.One of the most significant social developments of the 1890s, however, was also the most shameful. In an 1896 ruling in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court held that Louisiana's segregation laws were, in fact, constitutional and inaugurated over sixty years of de jure “separate but equal” segregation that was anything but. The doctrine of Plessy was the law until 1954 when it was invalidated by Brown v. Board of Education.

What this meant for Black moviegoers in the early decades of cinema has only recently been studied in key scholarly works like Jacqueline Stewart’s groundbreaking Migrating to the Movies. For a population who only saw themselves demeaned and dehumanized by the images of Blacks onscreen, moviegoing was a fraught, complex experience. Furthermore, many Black commentators of the time who subscribed to the ideology of racial uplift saw little value in motion pictures and urged Blacks to aspire to higher forms of culture in order to uplift themselves and the race in general.

Not only in the South but also in the North, racist theater owners found many ways of discouraging Black attendance. Black patrons were relegated to the very worst seats in the gallery—the cheapest seats in the house—though they were often charged the price of a premium ticket. Or they would be allowed to attend screenings only after the final “Whites Only” show, a custom that soon became known as “the midnight ramble.”

For a harrowing account of the Black filmgoing experience in the segregated South, I urge you to read The Warmth of Other Suns (2011), Isabel Wilkerson’s masterful history of the Great Migration, which traces the movement of blacks to northern and western urban centers during the first decades of the 20th century.

Recommended reading: Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, Migrating to the Movies; Cinema and Black Urban Modernity (University of California Press, 2005).Recommended reading: Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011).The Segregated Movie Palace Experience

Segregated theater. [Young Men at Base of Exterior Stairway to Movie Theater Balcony, Anniston, Alabama, 1936]. Peter Dekaer. (Copyright, Estate of Peter Dekaer. Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Galley, New York)One moviegoer vividly recalled his theater-going experiences. Mad about the movies, nothing could stop him from dressing up and visiting his local theater on a regular basis, not even the humiliations he knew were awaiting him once he arrived.

Forced to wait at the ticket window as white patrons were served first at a separate window—and served by the same ticket seller, who would swivel on a stool from one window to the other—he had to use a separate entrance and then climb a reeking set of stairs befouled by backed-up toilets.

In the uppermost sections of the theater, where the sightlines were poor and the sound barely audible, he would take his seat among his Black neighbors. Nevertheless, despite the humiliations, he persisted in participating in the communal experience of cinema.

Opening night of the Rex Theatre, Hannibal, Missouri, April 4, 1912. (Courtesy Hannibal Free Public Library)Segregation and the desire for more honest, more authentic cinematic depictions of Black life led to the rise of a fascinating cycle of so-called “race” films that featured Black performers. Those race films are the subject of the Finger Lakes Film Trail’s previous series of talks, all of which are available online. To quote from the website: “To appreciate where we are today in terms of racial relations and civil rights, we—as individuals, as a community, and as a nation—must have a better understanding of how, historically, we got here. Race Films/Race Matters is an attempt to do just that: to use race films as a starting point for necessary, informative, and provocative conversations about race, racial tension, and racial discrimination in America today.” If you check out any one of the resources I’ve recommended today, please make it this one.

PROGRAM LECTURER

Ken Fox

Ken Fox is the Head of Library and Archives at the Richard and Ronay Menschel Library at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York. Formerly the associate editor of The Motion Picture Guide and a film reviewer for TV Guide, he is a graduate of the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation and holds a master's degree in Information Science from the State University of New York at Albany.

The Finger Lakes Film Trail program series Making Noise About Silent Film: Conversations About Cinema, Culture, and Social Change is made possible by an Action Grant from Humanities New York, with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Humanities New York has been a valued financial supporter of the Finger Lakes Film Trail since its inception in 2018.